It’s Not What It Looks Like

Those tricksy skeuomorphs are everywhere

Once you start noticing them, you see them everywhere: fake wood, fake leather, fake fur, the rivets on your jeans, and a plethora of other decorative details. I first became aware of the concept of skeuomorphism while studying for a diploma in Field Archaeology. Drawings of clay vessels produced by the early Bronze Age Bell Beaker culture showed them incised with patterns resembling basketwork, a visible reference to an earlier technology. Elsewhere, vessels made of bronze plates were copied in clay, complete with imitation rivets.

The term, derived from Greek σκεῦος (‘implement’) and μορφη´ (‘form’), refers to a decorative feature that imitates an obsolete structural element of an object, and was coined by the antiquarian Henry Colley March in 1889.1 The OED defines a skeuomorph as ‘An object or feature copying the design of a similar artefact in another material, while Collins English Dictionary describes it as ‘A functional item redesigned as something decorative’.

These Bronze Age examples illustrate two functions of skeuomorphism: to make a new technology acceptable by replicating traditional forms, or to imitate a higher-status material, in this case metal, in a cheaper one, clay. Responding to something deeply embedded in the human psyche, both persist to this day.

Turn over an old-fashioned teaspoon and you may find a shield-shaped feature where the bowl joins the handle. Before the Industrial Revolution, this was where the two parts of the spoon were soldered together; once spoons were mass-produced, it became a moulded ornament with no functional purpose. Light bulbs for chandeliers and sconces are still made in the shape of a candle flame, while more recently, fashionable LED bulbs reproduce the effect of old Edison filament lamps. The cuff buttons on men’s jackets originally allowed the wearer to fold back the sleeve when working or eating, but are now purely decorative and can’t be undone. And then there are those annoying fake pockets that are no use for anything.

Many bollards in British cities look like cannons set into the ground, their mouths stopped by a ball. The practice of re-using surplus naval cannons for this purpose, with cannonballs fixed into their mouths to deflect rainwater, may date back to the 17th century, and became widespread during the Napoleonic Wars. Some of these original cannons still survive today but many bollards have been manufactured since then in imitation of the traditional form, and were never fired.

One skeuomorph that appeals to me as a bibliophile is the coloured cloth band that appears at the top of a book’s spine. Nowadays these are cut from a length of ribbon and glued in place to create an attractive finish, but they were originally an integral part of a book’s construction. The linen thread used to bind the signatures would be extended to the top of the spine and looped around a strip of vellum or card to create a headband. Firmly moored to the binding, it would allow a reader to pull the book from a shelf by its top without damaging the spine. Today’s ribbon bands, though pretty, offer no such reinforcement, as several books on my shelves sadly testify.

Computer technology has given skeuomorphism a new lease of life, albeit with a slight shift of meaning: the envelope icon to signify email; cc (carbon copy); folders; the waste bin; and cut and paste (I’m old enough to remember physically cutting up typescripts to reorder the paragraphs). So fast has been the speed of change that some elements of obsolete computer technology have already turned into skeuomorphs, such as the floppy disk icon – when did anyone last use one of those?

Colley March, H. 1889. ‘The Meaning of Ornament, or Its Archaeology and Its Psychology.’ Transactions of the Lancashire and Cheshire Antiquarian Society 7:160–192

‘The pleasure of studying, not the vanity of mastering, has been my chief aim.’

Jorge Luis Borges, ‘An Autobiographical Essay’, 1970

If you have enjoyed this post, please consider sharing it with any friends you think may be interested.

The Glass of Renaissance Fashion

Castiglione’s courtly conversations

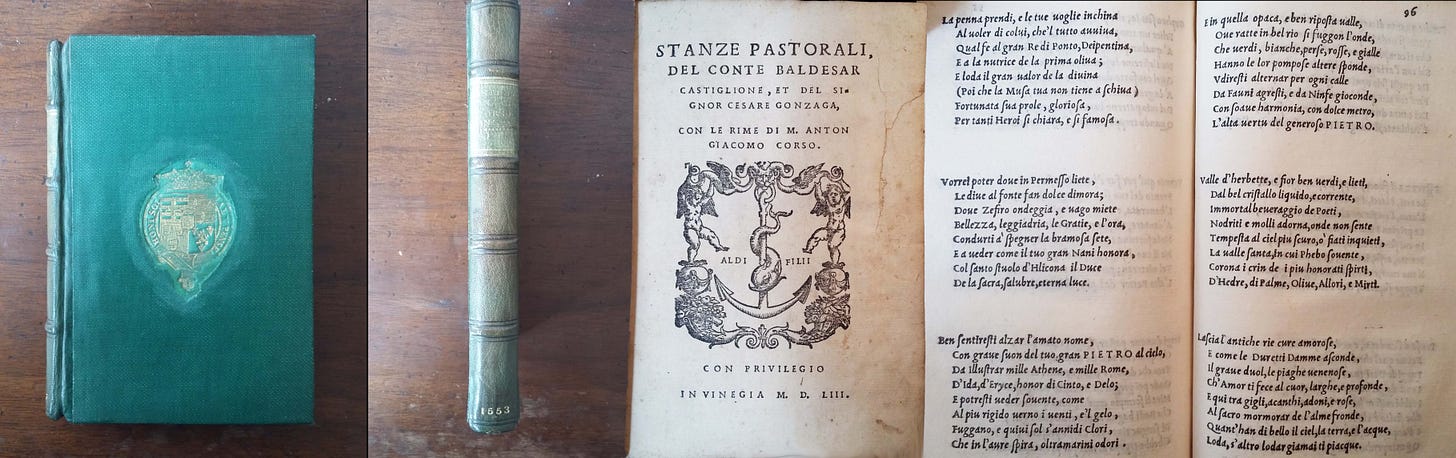

Rummaging in my bookcase recently, I came across a small duodecimo volume I hadn’t looked at for years. Bound in green 19th-century boards with royal arms, re-backed in green morocco and re-covered in buckram, it is a first edition of the Stanze Pastorali by Baldassare Castiglione, published in Venice by the sons of Aldus Manutius in 1553, ‘Aldi Filii’ printed either side of the firm’s famous symbol of a dolphin curled around an anchor. I paid £10 for it from a secondhand bookshop when I was a student many years ago. An internet search turned up a copy for sale by an antiquarian bookseller for no less than €5,500; mine is less than pristine, however, with title page torn and repaired and the first page of the index missing, defects that, in the demanding world of antiquarian book dealing, wipe a zero off its market value.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Notes in the Margin to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.