Breaking the Fourth Wall

The surreal mystery of Edmund Crispin

Researching the history of London’s historic Authors’ Club some years ago, I was intrigued to discover that its members included the crime writer Edmund Crispin, who joined in April 1955. Crispin is a fascinating character; under his real name Bruce Montgomery, he was also a prolific composer, writing the scores for the Carry On and Doctor in the House films. The old green Penguin editions of his novels list his recreations as ‘swimming, excessive smoking, Shakespeare, the operas of Wagner and Strauss, idleness, and cats’.

His crime novels, which feature the eccentric Oxford don and amateur sleuth Gervase Fen, have been praised by P.D. James, A.L. Kennedy and Val McDermid for their ingeniously intricate plots, surreal mystery and arch humour. In The Moving Toyshop (1946), for example, the celebrated but cash-strapped poet Richard Cadogan decides to take a holiday in Oxford. Arriving in the middle of the night after a much-delayed journey from London, he stumbles across an unlocked toyshop on the Iffley Road. Inside, he finds the body of a woman strangled with a length of cord, and is promptly knocked unconscious by an unseen assailant. On waking the next morning, he goes to fetch the police, but when they return, the toyshop is no longer there…

Dazed and doubting his own sanity, he enlists the help of his friend Fen, and they embark on a series of chases around Oxford, aided and abetted by an ever-growing band of hangers-on. Later in the novel, the toyshop mysteriously reappears on the Banbury Road, at the other end of town, before their adventures reach a climax in a fight on a funfair merry-go-round – a scene lifted wholesale (and uncredited) by Alfred Hitchcock in his 1952 film Strangers on a Train.

The novel takes its title from Alexander Pope’s The Rape of the Lock (‘With varying vanities, from every part,/ They shift the moving toyshop of their heart’), and is dedicated to his friend Philip Larkin, who makes a cameo appearance as a precocious undergraduate handing in an essay. The book is packed with literary references: a vital clue hangs on the limericks of Edward Lear, Fenn, making an incognito telephone call, pretends to be T.S. Eliot, and Cadogan, in a moment of reflection, recalls lines by Vaughan, Dunbar and Nashe (‘Dust hath closed Helen’s eye…’).

Furthermore, Crispin’s protagonists know that are characters in a work of fiction, as he breaks the fourth wall to draw the reader into complicity with his meta-textual pranks. When Fen and Cadogan are locked in a cupboard by a pair of heavies, the academic sleuth passes the time thinking up titles ‘for Crispin’: ‘A Don Dares Death (A Gervase Fen Story)’, ‘Murder Stalks the University’, ‘Fen Strikes Back’…

The effect is rather as if Italo Calvino had rewritten a novel by Dorothy L. Sayers. But for all his high jinks, Crispin – like all serious practitioners of crime fiction – does not diminish the horror of the act of murder: in a sombre moment toward the end of the book, Cadogan reflects on ‘the violent cutting off of an irreplaceable compact of passion and desire and affection and will’ as ‘a thrust into unimagined and illimitable darkness’.

Edmund Crispin. The Moving Toyshop. London: Penguin, 1958.

David Whittle. Bruce Montgomery/Edmund Crispin: A Life in Music and Books. Farnham: Ashgate Publishing, 2007.

‘Who are we, who is each one of us, if not a combinatoria of experiences,

information, books we have read, things imagined?’ ― Italo Calvino

If you have enjoyed this post, please consider sharing it with any friends you think may be interested.

A Dance to the Music of Time

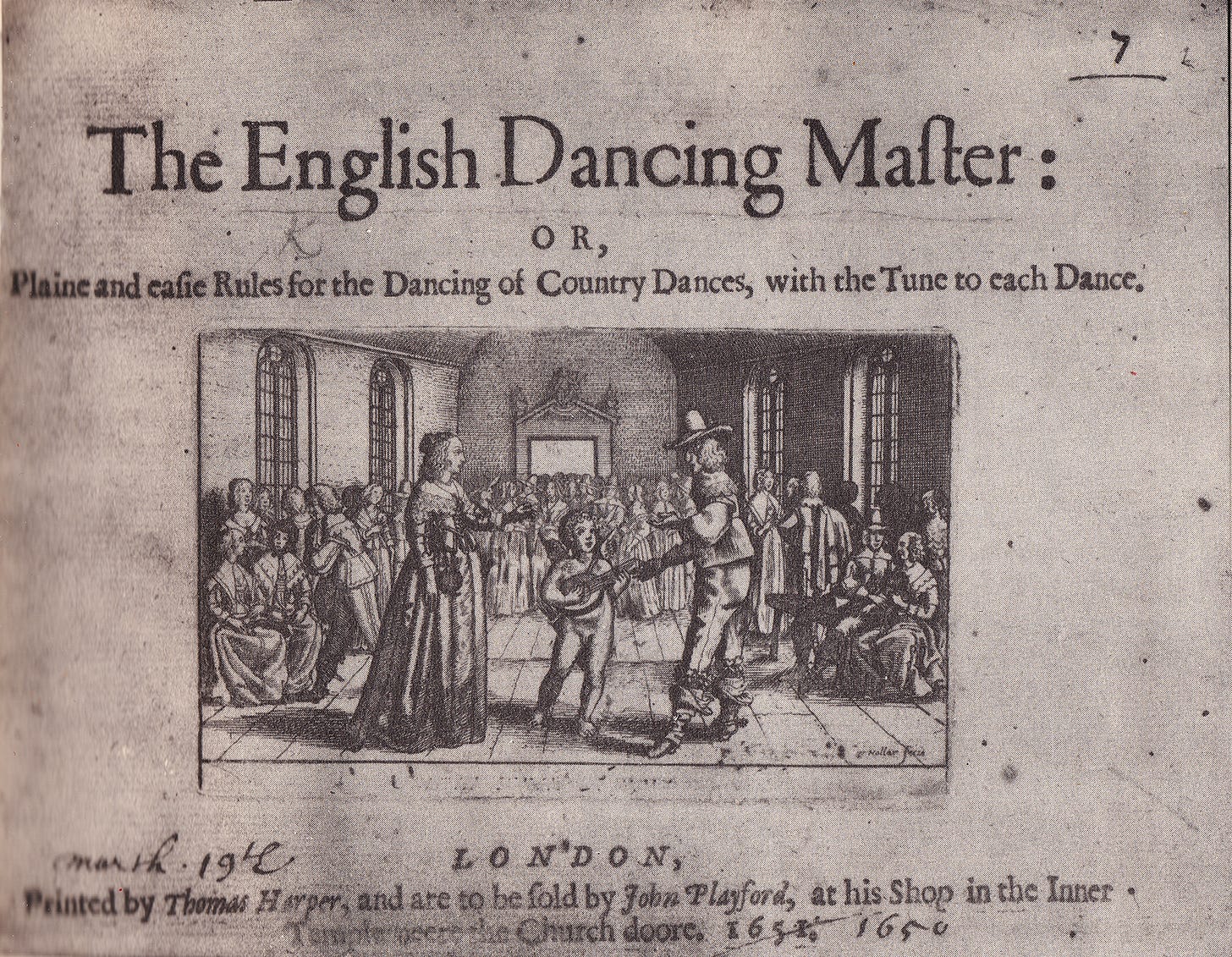

John Playford’s English Dancing Master rediscovered

I have no recollection of when or where I bought it, but one of the more curious and attractive books on my shelves in a 1933 reprint of John Playford’s The English Dancing Master, originally published in 1651. Nor can I remember how much I paid for this delightful book, though I’m sure it was more than the original twelve and six, but considerably less than the £200 this edition fetches online today.

The original publication date somewhat gives the lie to the idea that the Puritans managed to stamp out all forms of entertainment – though Playford acknowledges in his address ‘to the Ingenious Reader’ that ‘these Times and the Nature of it do not agree’, but news of a ‘false and surreptitious’ pirate edition has compelled him to publish.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Notes in the Margin to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.